Baltic House Theatre-Festival Premiere – February 20, 2009 Based on the novel by Janusz Leon Wiśniewski. Director – Henryk Baranowski (Poland) Stage Director – Andrey Nikitinskih Production Designer – Alexey Porai-Koshits Director of Photography, Video Art, Editor – Svetlana Bakushina Costume Designer – Irina Tsvetkova Choreography – Sergey Grizay Music Selection – Mirosław Jasieński (Poland) Lighting Designer – Konstantin Udovichenko Musical Group Leader – Alexander Chernyshev

Theater and Film Intertwined

THE INVITATION

Henryk’s email arrived with an intriguing invitation: join another ambitious project at St. Petersburg’s prestigious “Baltic House” Theatre. This time, we would tackle “Loneliness in the Net,” Janusz Leon Wiśniewski’s bestselling novel exploring the complex terrain of virtual love relationships.

A DUAL REALITY CONCEPT

Henryk’s vision was cinematically bold. He wanted to create a multilayered production where film scenes shot on location would synchronize perfectly with the live theatrical performance. The concept was elegantly structured: what unfolded on stage would appear as reflections or memories of the protagonist, who recounts his life story to a homeless man at a train station, moments before contemplating suicide. Meanwhile, on screen, these same memories would bloom in vivid color, revealing the “reality” behind the reminiscence.

MY ROLE & THE AUTHOR’S CAMEO

The technical and creative responsibilities being offered were substantial. I would oversee all video projections, direct and film scenes with the actors, handle all editing, and create original video art for the screen positioned above the stage. Adding literary gravitas to this experimental approach, Wiśniewski himself was expected to attend the premiere and even make a special appearance, embodying the homeless man character during the play’s conclusion.

A CREATIVE BREAKTHROUGH

The conceptual fusion of theater, cinema, and literature promised something truly innovative. As I read through Henryk’s proposal, excitement built within me—this project represented exactly the kind of boundary-pushing work I had hoped to create.

ART AND MATHEMATICS

PREPARATIONS

This was my first large-scale project with such a high level of responsibility—although I had already worked on several sizable television productions. I began with preparations. First, I made a list of everything I’d need for the production: a camera with a specific set of lenses, a powerful computer with professional video editing software installed, lighting equipment, and so on.

MEETING THE TEAM

Then I flew in for a meeting with the creative team and the theatre’s director, Sergei Grigorevich Shub. I was glad to meet him, the resident set designer Aleksei Porai‑Koshits, costume designer Irina Tsvetkova, and deputy director Marina Aronovna Belyaeva. She was the heart of the theatre—solving problems in the blink of an eye. Marina informed me that the theatre wouldn’t be able to provide filming equipment or a computer, and asked if I could bring my own.

LIMITED RESOURCES

Bringing all the necessary equipment was out of the question. So I suggested that we either rent the required gear and use the theatre space for filming, or rent a TV stage instead. We eventually agreed to shoot part of the film in the basement beneath the stage, and the remaining scenes at a TV studio. And then the rehearsals began.

STAGE DESIGN

The stage was designed to resemble a train station, where the main character tells his entire story. There were supposed to be tracks and a “train plate” that could slide back and forth. All of his “memories” (scenes from his life) were to include train station elements—like chairs and tables wrapped as if ready for transport.

Henryk wasn’t comfortable with the large stage since the scenes were very intimate and personal. The set designer came up with a creative solution: divide the stage into three parts. Each part would be a movable “train plate” with tracks. This allowed scenes to be staged on separate plates and moved into place as needed.

INTIMATE PERFORMANCE

Henryk also instructed the actors to speak in their natural voices—no theatrical projection or “stage shouting.” To achieve this, each actor had a microphone attached. Additionally, each moving plate had its own screen with a projector—adding three more screens to the one already above the stage.

Calculating the Impossible

Here’s where it gets interesting—and no one seemed to notice this. I was working with highly creative people, but they usually don’t think in numbers.

The play’s total length was 3 hours and 30 minutes. With four screens showing projections, that’s 3.5 hours × 4 = 14 hours of video content. Considering the alternative cast, we needed to shoot and edit every scene twice. So double that: 14 × 2 = 28 hours of final video.

Now imagine how long it takes to film and produce 28 hours of edited, synced, green screen–removed, and composited high-quality footage—essentially the equivalent of a 28-hour feature film. And how many professionals are usually needed to accomplish that? Now comes the most interesting part. Let’s see if I can pull it off in just 25 days.

An Unexpected Assistant Steps In

Henryk always needed someone to rehearse with the actors when he couldn’t attend a rehearsal himself—just to repeat and run through what he had already staged. He asked me to do it, but I simply couldn’t; I was too busy with my primary work on the video projections.

That’s when Andrey Nikitinskih appeared—a young actor who had recently moved to St. Petersburg from Tomsk, where he had previously worked with Henryk. Henryk liked him a lot, and even though Andrey wasn’t part of the theatre’s ensemble, Henryk gave him several roles, including that of a Polish Catholic priest. He also appointed him as second director to assist during rehearsals.

When Henryk Disappeared for a Day

I soon understood why Henryk needed help. One morning, as usual, I knocked on his door so we could go for breakfast. He didn’t open for a long time. I waited outside, hearing faint sounds from within. Eventually, he opened the door. He looked strange—tired, with heavy, sleepy eyes, and a greyish complexion. He spoke very softly and told me he was staying in, that he needed rest, sleep, and time to meditate.

That day, he missed the morning rehearsal and only came to the evening one—but even then, he wasn’t himself. After a short attempt, he stopped everything. He apologized and said he wasn’t in the right state of mind, that he couldn’t be of any help today. “I won’t be good for anything,” he said, “I just want to talk or read something.” But the next day, he was back to full strength—energetic, cheerful, and ready to work again.

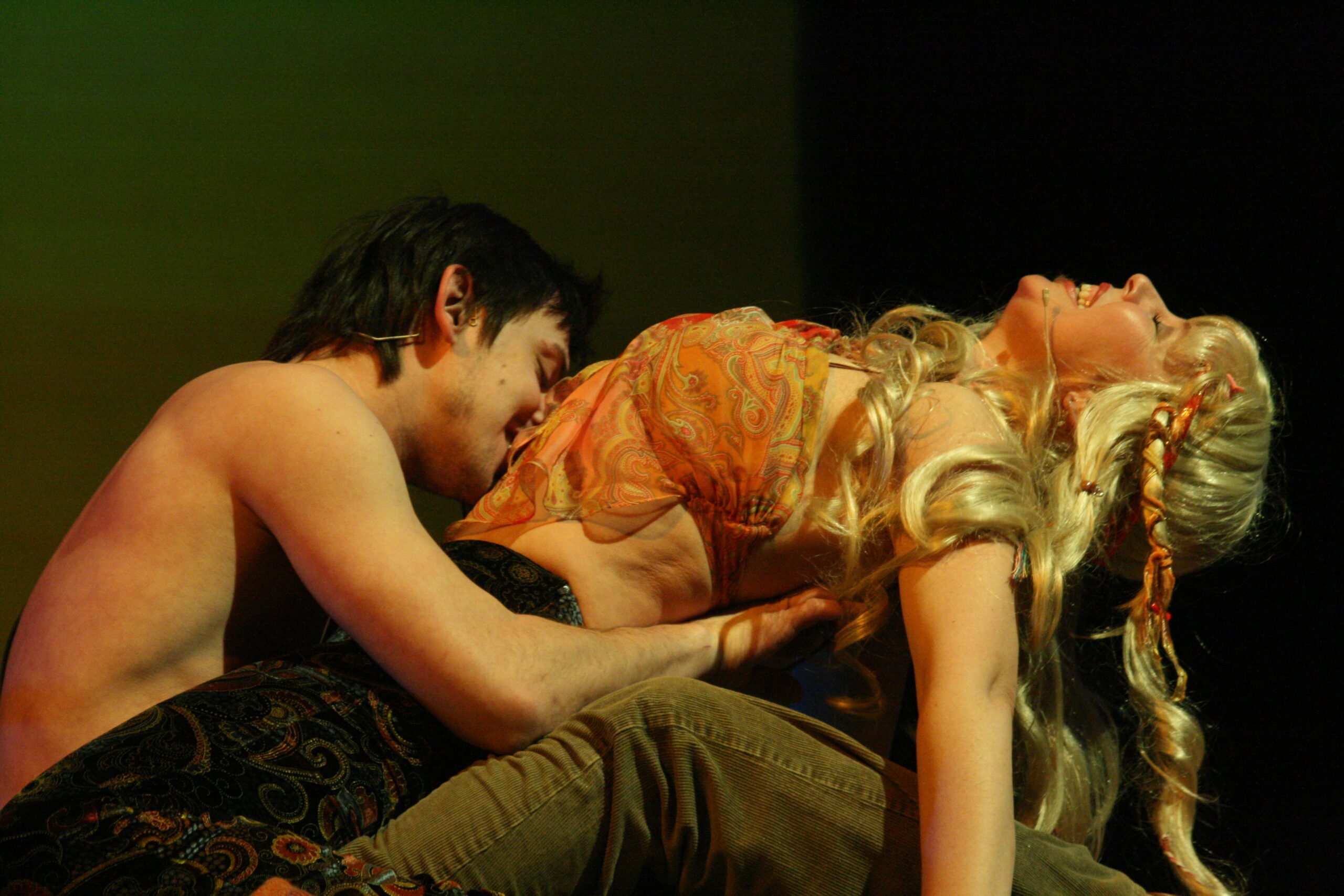

The Scene That Shocked the Room

That day’s rehearsal was supposed to focus on a scene taken directly from Wiśniewski’s novel—a moment in a Paris hotel where Eva, the main character, is waiting for Jakub and masturbates. But things went very wrong. The actress refused even to begin the scene. Visibly upset, she left the rehearsal, and everything came to a sudden halt.

Henryk was baffled. He couldn’t understand what had gone wrong—he was following the novel exactly as written. All the actors had read it before signing their contracts. He didn’t understand why a theatre would choose a story the actors couldn’t bring themselves to perform.

A Cultural Misunderstanding

Back in his office, Henryk had to rethink the entire scene. Replacing the actress wasn’t an option. He simply couldn’t grasp why she had reacted this way. What he didn’t know—what most outsiders don’t know—is that in Russia, anything related to sex is still considered a taboo, even as a topic of private conversation.

There’s a cultural discomfort around sexuality, and most Russians struggle to talk openly about sex, even with their own partners. So for an actress to perform a masturbation scene, even in a symbolic, theatrical context, in front of her colleagues—it was deeply uncomfortable. For her, it was likely a moment of personal shame, something “unthinkable.”

LOST IN RE-TRANSLATION

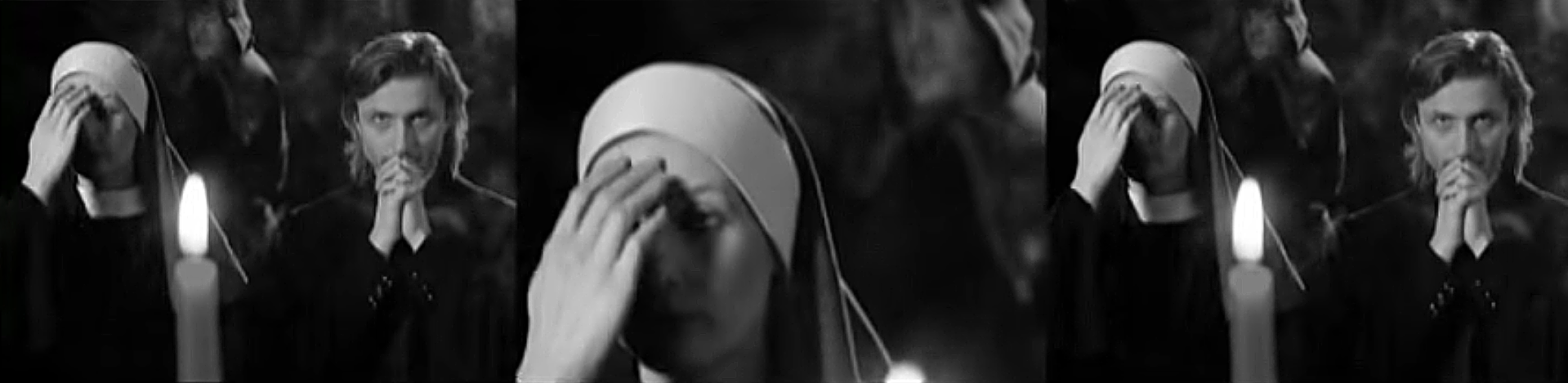

A Gothic Church and Censorship

We found a beautiful Gothic church for filming the priest’s storyline. It wasn’t open to the public, and inside, the walls displayed prints by contemporary artists exploring the theme of Christ. The church hadn’t been renovated, which gave the interior a rich, textured atmosphere—and the basement was exactly what we had in mind for the scene. The church belonged to a German man who happened to be there when we visited. We explained the plot and asked for permission to film. He agreed.

The private Gothic church in St. Petersburg

The private Gothic church in St. Petersburg

The Day Everyone Forgot Their Mother Tongue

The next day, a large bus pulled up to the location—twenty crew members, equipment, the works. But things started off on the wrong foot. Henryk, the production manager, and I were asked to come inside for a conversation first.

We were greeted by the German man and a younger woman. Henryk, who had lived in Germany for many years, naturally started speaking in German. The man answered—in perfect Russian. He introduced the woman as Polish. Henryk immediately switched to Polish, but she replied with just a few words—heavily accented in Russian. They both insisted on continuing the conversation in Russian. It was comic.

Clash of Perspectives

The woman had read the novel carefully and had clearly done her research. She didn’t like the idea of filming that particular scene inside the church—where Father Andzhey, already on the brink of insanity, tattoos “There is no God” on his hand. She agreed to let us shoot there, but only under one condition: we would have to show her the footage afterwards and could only use it if she gave her approval.

Henryk was firm. “I’ve had enough censorship back in the Soviet Union,” he said. And with that, we left the location. On the way back, we restructured the plan and found another solution. The scene was shot elsewhere, with a new approach.

Behind the scenes. Filming under the stage

The Costume Crisis (and How We Got Around It)

We were trying to schedule the shoot for the remaining scenes, but it turned out the costumes would only be ready ten days before the premiere—and we couldn’t film anything without them. Still, Irina Tsvetkova, the costume designer, managed to push the costume department to finish a few pieces early, at least for the main characters. So we decided to film some scenes in specially prepared spots inside the theatre, and once all the costumes were ready, we’d move to the studio to shoot the rest. Days were for shooting, nights for editing. So far, everything was going fine.

Studio Shoot Day: When Things Got Weird

Then came the studio shooting day—and from that point on, things started to get weird. We had rented a large television studio with a full crew, most of whom seemed to look at me with a touch of irony. The lighting technician, in particular, kept throwing out pointless technical questions, clearly just testing whether I knew what he was talking about.

We had hired two camera operators—plus myself to operate 3 cameras. Within half an hour, Henryk sent the first one “to hell,” and about thirty minutes later, the second guy followed. Then Henryk declared, loud and clear (making sure every technician could hear), that no lights or cameras were to move without the direct order of this girl—and pointied at me. The lighting guy ran out of questions and stayed quiet for the rest of the day.

Three Cameras, One Operator

Until the camera guys’ replacements arrived, I had to operate three cameras at the same time—one positioned still on a wide shot while I operated the second one. In general, there was a very tense atmosphere due to the large number of actors, costumes, and we even had a real mini pig there!

The Vanishing Assistant

Another problem was the director’s assistant, a girl appointed by the theatre. She would do everything possible to hide from Henryk, avoiding any meetings or conversations and not even answering the phone when needed.

“Father Andzhei” film

In one week, I completed the final film about the love story of the Polish Catholic priest, Father Andzhei. It turned out great—especially with the parallel action happening on stage. While I was working on all the other scenes, time seemed to go faster and faster. And here we were already rehearsing on the big stage, where we really needed all the projections to see the full picture — and, no surprise, they were still nowhere near finished.

Burning the Midnight Oil

Although I was sleeping only from 6:30 AM to 9 AM, and because I was freezing, I would take the hot laptop charger to bed with me to warm my feet. The rest of the time I was glued to my computer, editing and compositing the green screen scenes. Time was evaporating, and my 32-hour feature film still felt light-years away from completion. Henryk’s mood darkened by the day, throwing lightning bolts at everyone who crossed his path. We had precious few projections ready, with the majority still unfinished. I was drowning in footage.

“Les Saboteurs” Within

Nevertheless, the worst was yet to come. My colleagues from the video department were struggling with connecting four projectors to display different video channels simultaneously. They convinced the director to purchase an extremely expensive video mixer that supposedly had four outputs and would solve all our problems. They received the mixer—except it had four inputs, not outputs. (Just don’t tell the director.)

Instead of helping the production succeed, they were taking actions that would ensure its failure. They harbored an inexplicable hatred toward me until one of them accidentally revealed their motivation: they believed I was being paid millions while they survived on meager salaries.

I learned from Henryk how to command respect through my voice—how to speak in scary, authoritative tones that would spur them into action. I perfected this skill quickly, yelling with increasing volume and intensity each day, occasionally punctuating my commands with expletives when necessary. It worked most of the time. Still, this local “all-guys team” continued their subtle sabotage, making every step forward feel like wading through quicksand.

A Silent Understanding

As the rehearsals continued, the projections slowly began to appear—bit by bit. Henryk liked everything I created. It was an unusual kind of understanding: somehow, almost magically, I always knew exactly what his vision was, even though he never gave me specific instructions. He never criticized my work—on the contrary, he seemed to genuinely enjoy every pixel of it. Being so deeply appreciated felt rare and special. It was a truly unique collaboration.

THE PRESSURE BUILDS

But as pressure mounted and the premiere approached, the atmosphere turned heavy with that familiar sense of impending failure. And, of course, the saboteurs were quick to point fingers—at me.

Emergency Backup Team

The only way forward was to replace them. I called an old university friend who had moved to St. Petersburg and asked him to come immediately—bringing along his friends and their computers. Within hours, three guys were crammed into my hotel room, each working on two laptops, editing the remaining footage. One of them even had a wife in labor at the hospital that day.

Sleep? Never Heard of It

I hadn’t slept properly in weeks. At one point, Henryk came in to talk, and I fell asleep mid-conversation—that’s how exhausted I was. For the rest of the week, the guys set up base in my room, taking turns editing and napping on my bed.

THE NEW DEPARTMENT

Eventually, we replaced the entire video department with my friends. They worked fast, with precision and zero rest—just occasionally asking for more money. Which, of course, I paid out of my own pocket. I just wanted to get out with my sanity—and maybe my shoes.

THREE DAYS BEFORE THE PREMIERE

We were still working. The air was electric, heavy with exhaustion, tension, and hope. Tickets were sold out. Not a single seat left. Then Henryk quietly entered my room and said, “My wife is arriving for the premiere. She must not know anything about the problems we’ve had.” No pressure.

PREMIERE DAY

Morning. My three friends and I were still working.

Evening. Still editing.

The show had already begun. We were racing against time, fixing the last cuts while the stage lights were on and the first lines were spoken. And then—the final scene. A homeless man appears, and the screen was meant to fall like a curtain, revealing the image of the train station. Janusz Leon Wiśniewski, playing the role, stood frozen in half-light because the screen jammed halfway. The assistant had messed up again.

But Henryk? He turned to me and whispered, delighted:

“It’s better this way. It makes more sense.”

THE IMPOSSIBLE MASTERED

The show ended in triumph. It was a roaring, unforgettable success—one of those moments you know will live forever in people’s minds. I returned to my room in silence, too exhausted to feel joy, only the kind of relief that borders on collapse. Then there was a knock. I opened the door.

There was Henryk—radiant, beaming, full of energy I couldn’t fathom. He grabbed my shoulders, smiled like a father proud of a miracle, kissed my forehead, and said something so kind and simple I almost cried right there.

Henryk did something impossible that night—not just finishing the show, but making it soar. He had a rule: anyone who used the word “impossible” would be fired. For him, a true creative mind was defined by one ability above all: to find a solution. Any solution. Always.

WHAT I LEARNED FROM HENRYK

I learned to work through fear.

To observe and listen.

To give everything, even when there’s nothing left.

To trust instinct.

To take risks.

To believe in the vision, even in the darkest hour.

And most of all—

There is no “impossible.”

Because he showed me that the impossible can be done with fire, with love, with madness, and with art.

press conference

Pictured at the desk, from left to right: Theater and film director Henryk Baranowski, Press Conference Moderator, writer Janusz Leon Wiśniewski, and Director of the Baltic House Theatre, Sergei Grigorevich Shub, 2009

Scenes from the Play in a Playlist

A selection of original films shown during the play, along with handheld footage from the premiere night, recorded live from the backstage projection room.

Stage Views

Photographed from the backstage projection room by me. Close-ups by the theater’s resident photographer, Yuri Bogatyryov

Characters & Cast

-

Eva – Alla Eminceva / Tatyana Kuznetsova

-

Jakub – Valery Solovyov

-

Young Jakub – Roman Dryablov

-

Natalia, Sister Anastasia, Dancer – Varvara Markevich

-

Natalia’s Father, Bartender – Leonid Alimov / Anatoly Dubanov / Alexander Pavelyev

-

Wanda, Natalia’s Mother – Valentina Vinogradova / Irina Konopatskaya

-

Granddaughter on the Train, Ivona, Kim – Inna Volgina / Alexandra Kuznetsova / Yulia Men

-

Asya, Psychologist – Victoria Zhilina / Irina Murtazaeva

-

Belgian, Youth in Internet Café, Student in Paris, Orderly, Porter – Alexander Chernyshev / Oleg Korobkin

-

Asya’s Husband, Orderly, Porter, Guard, Airport Security – Anatoly Dubanov

-

Homeless Man, Old Man on Train, Jacek, Ambassador, Security Officer – Leonid Alimov / Alexander Pavelyev

-

Virginia – Leonid Alimov / Roman Dryablov

-

Eva’s Husband – Leonid Alimov / Andrey Nikitsinsky

-

Ksiądz Andrzej, Jim – Andrey Nikitsinsky

-

Old Woman on Train, Nurse, Airport Security – Galina Demidova

Film Cast

-

Psych Ward Nurse, Kim, Flight Attendant, Widow – Yulia Men

-

Nurse, Widow’s Maid – Galina Demidova

-

Corporal, Young Jacek, Eva’s Husband – Leonid Alimov

-

Blues Singer, Student, Porter – Alexander Chernyshev

-

Psychologist – Irina Murtazaeva

-

Airport Officer – Anatoly Dubanov

-

Ksiądz Andrzej – Andrey Nikitsinsky

-

Anya, Jacek’s Daughter – Valeria Popova

-

Airport Clerk – Natalia Vinogradova

Also featuring: Roman Polyakov, Timur Vigilyansky, Alexey Platunov, Alexander Shvedov, and the mini‑pig Josephine.